Return to Standish families of the Manor of Duxbury.

![]()

The final years of the Manor of Duxbury Lancashire England.

The Mayhew Family & The Mason Family of Ireland.

LINK -:

The final years of the Manor of Duxbury part 2 .

![]()

1898. Walter Mayhew Lord of the manor of Duxbury 1898 - 1933.

Arms of Mayhew

Mr. Walter Mayhew was descended from a brother of Thomas Mayhew the colonial governor in 1641 of Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, and the Elizabeth Islands United

States of America

Mr. Walter Mayhew. See Burke's Landed Gentry and Fox-Davies Armorial Families.

In February 1898 a Wigan solicitor, Walter Mayhew, purchased Duxbury

Hall, its park and Anglezarke Moor. Walter’s family were of Suffolk yeoman

stock and he liked to recall that a Mayhew is listed amongst the passengers on

the Mayflower which took Captain Myles Standish and the Pilgrim Fathers

to the New World in 1620. Walter always felt a sense of history and was keen to

supply information for the local

compilation of the Victoria County History. This may explain one

reason why he came to Duxbury and secured the title of lord of the manor’ for

his son. Then again, social ambition may have played some part - the Wigan

solicitor had already been mayor of the town in 1876-7 and rented Euxton Hall

for a time. Opportunity certainly existed; his firm had handled mining leases

for the Duxbury estate and he would be well

aware of the attempts to sell off the lands since 1891. Taking a kindly view,

it would be relevant to mention Walter’s wife. Annie. She had enjoyed life at

Euxton Hall, becoming an important patroness of the local church, indeed

saviour of its roof. Her sister was a resident at nearby Gillibrand Hall. Since

1893 Walter and Annie had lived in London, but rents were high and Annie was

suffering from ill health. A return to a country seat of their own in

Lancashire may have been Walter’s last great gesture for his wife. Tragically

she died in September 1898 of what is simply described as ‘internal disease’.

Tradesmen in Market Street drew their blinds as she passed from a funeral

service at the parish church to a family vault at Chorley cemetery. The family

and local worthies preceded the ninth carriage taking the servants from the

Hall. The white blooms of Duxbury were much commented upon. Annie's

memorial stone in Chorley cemetery hints somewhat at her patient suffering -::

Walter carried on at Duxbury until his death in 1918. His son, Percival Sumner Mayhew, had been a globe-trotting photographer but at the mature age of forty-three was induced to take a wife, Constance Evelyn King of Quebec and London, a lady of no little beauty and social standing. The wedding, at the end of January 1907, was held in St Margaret's Church, Westminster, a venue which hints at the political connections of the bride's father. The bride wore rich satin and carried an ivory and gold prayer book, a gift from her new husband. A reception was held at Queen Anne Mansions for three hundred guests before the happy couple departed for a honeymoon on the Italian Riviera. A shadow was cast by news of the death of a sister of one of the Hall servants; Percival penned a sympathetic note and recommended a short holiday.The homecoming of the happy couple was a splendid occasion. The north lodge gate had sprouted an arch of yew to frame the welcoming tenants and twelve strong locals were determined to draw the carriage along the drive. – by Bill Walker.

Duxbury Hall in 1898 when it was purchased by the Mayhew family.

Duxbury North Lodge in 1907 decorated for the return of Percy Mayhew and his new wife.

Thomas Mayhew of - Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, and the Elizabeth Islands United States of America.

New York Herald Tribune 25th December 1932.

Mayhew, Thomas

Mayhew, Thomas (bap. 1593, d. 1682), colonial

governor and missionary in America, was baptized on 1 April 1593 at St

John the Baptist parish, Tisbury, Wiltshire, the son of Matthew Mayhew (d.

1612?), farmer, and Alice Barter. Thomas was apprenticed to a mercer in

Southampton, and completed his apprenticeship in 1621. About 1619 he married

(according to tradition) Abigail Parkus or Parkhurst; they had one son, Thomas

jun. In 1631 he agreed to go to Massachusetts Bay and work as the agent of

Matthew Cradock, a former governor of that colony and then a prominent London

merchant who owned (among other enterprises) a plantation at Medford. Mayhew

settled there, managed Cradock's plantation, mill, trading house, shipbuilding,

and fishing fleet, and became friends with John Winthrop jun., governor of

Connecticut. About 1636, following a visit to England during which he married

his second wife, Jane Gallion Paine (with whom he had four daughters), he left

Cradock's employ and moved to Watertown. His extensive merchant connections

made him one of the wealthiest men in town, and he was elected selectman and

delegate to the general court.

In 1641 Mayhew purchased, from Ferdinando Gorges and Henry Alexander, third

earl of Sterling, competing patents to Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, and the

Elizabeth Islands. His son and a group from Watertown settled on the Vineyard

at what is now Edgartown. Mayhew himself did not move to the island until 1646.

By that time his son was already an active missionary among the Wampanoag

Indians on the islands, becoming their doctor, minister, and teacher. Mayhew

followed his son in becoming fluent in the Wampanoag language and extended his influence

among them. In 1657, after his son was lost on a voyage to England, Mayhew took

over the missionary work, preaching at least one day a week and often acting as

a judge or adviser to American Indian communities and converts. Backed by the

Boston-based Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, he followed a policy of

recognizing the American Indian leaders' traditional authority while gradually

building Christian Indian communities. It is this policy, and the Mayhews'

ability to maintain good relations with the Vineyard natives, which still draw

the admiration of historians. The peace on the island may, however, have

cloaked a muted conflict between the Christian Indians and Mayhew's support for

traditional native rules and polity.

Within a few years of his arrival on his island Mayhew exercised extensive

executive power over that tiny English community, governing with a small

advisory council. In the wake of his son's death he became even more

autocratic, as a sole ruler in both magisterial and executive capacities. But

in the 1660s he confronted various challenges to his proprietary authority.

First, in 1661, he noticed enough discontent to feel it necessary to have some

settlers sign a form that acknowledged his rule. Several years later two powerful

Englishmen pressed competing patents: James, duke of York (whose brother

Charles II had rolled the Vineyard and Nantucket into his rights to New

Netherland), and the heir to Gorges's patent—also confirmed by the king. For

the rest of the decade Mayhew waited resolution of the issue (and tried to

ignore the letters from James's representative, the governor of New York) while

maintaining daily control of the island. In 1671 he was summoned to New York by

a new governor, Francis Lovelace, to defend his claims. At the hearing Mayhew

and Lovelace worked out an arrangement by which the island ruler would

acknowledge York's sovereignty in exchange for a lifetime appointment as

governor of Martha's Vineyard. While the English on the islands would elect

magistrates and a general court, Mayhew retained effective control by presiding

over both. He even persuaded the governor to grant him a manor—the only one in

New England—incorporating the Elizabeth Islands and the current boundaries of

the towns of Chilmark and Tisbury.

In 1673, after receiving word that the Dutch had retaken New York, a group of

Vineyard settlers challenged Mayhew's domination. They set up their own

government, and applied to Massachusetts for recognition, but without success.

After the English regained control in October 1674 and reconfirmed Mayhew's

rule, he took revenge by seizing the estates of his wealthier antagonists, and

imposing fines and disfranchising his opponents. But the rumblings of

dissatisfaction continued, even after Thomas Mayhew's death on 25 March 1682 at

Edgartown, Martha's Vineyard. His grandson Matthew, who had been his steadfast

assistant, succeeded him and continued the family's control until 1691, when

the island was incorporated into Massachusetts by a new charter. The family

would also continue as missionaries to the Indians on the Vineyard, a role that

was apparently a key support for their authority on the island. While the

Mayhew family lost much of their political power, Thomas's legacy allowed them

to dominate the island's society and economy for several generations.

Daniel R. Mandell

C. E. Banks, The history of

Martha's Vineyard, Dukes county, Massachusetts, 3 vols. (1911), 1.104–81 ·

L. C. M. Hare, Thomas Mayhew: patriarch to the Indians (1932) · C. Mather,

‘A brief narrative of the success which the gospel hath had among the Indians

of Martha's Vineyard, and the places adjacent in New England’, Magnalia

Christi Americana, 2 (1853), 422–46, esp. 422–37 · M. Mayhew, A brief

narrative of the success which the gospel hath had among the Indians (1694)

· L. Travers, ‘John Cotton, Jr., among the Indians: Martha's Vineyard,

1664–1667’ [presented at ‘Microhistory: advantages and limitations for the

study of early American history’, 15–17 Oct 1999, University of Connecticut]

Jonathan Mayhew , born on 8 October 1720 at Chilmark, Martha's Vineyard,

Massachusetts, USA.

Mayhew, Jonathan (1720–1766), Congregationalist minister in

America, was born on 8 October 1720 at Chilmark, Martha's Vineyard,

Massachusetts, the youngest child of Experience Mayhew (c.1674–1759), a

missionary to the American Indians, and his wife, Remember Bourne (c.1682–1722).

Jonathan's father and three generations of Mayhews before him had been

missionaries to the island's American Indians. He received his education on the

island until he entered Harvard College in 1740. Having heard his father preach

a practical Christianity to the American Indians, he was ready to read the

works of the rationalistic archbishop of Canterbury John Tillotson and the

liberal English clergyman Samuel Clark. Upon graduation with honours in 1744 he

received grants from the Saltonstall Foundation which enabled him to continue

his studies at Harvard for another three years; he gained a master of arts

degree in 1747.

When Mayhew left Harvard he was called to Boston's ten-year-old West

Congregational Church, which he served for the rest of his life. His

parishioners were primarily upper- and middle-class merchants whom his

predecessor had accustomed to hearing presentations of liberal theology. In

this setting Mayhew preached his rational religion at Sunday morning and

afternoon services. Although Boston's Congregational clergy often exchanged

pulpits, Mayhew's unorthodoxy prevented most others from inviting him. About

1756 he married Elizabeth Clarke (c.1734–1777).

Always controversial, Mayhew undermined the pillars of Calvinistic puritanism.

Although he emphasized the ultimate power of God, his was a reasonable and

benevolent deity. He rejected the doctrines of original sin and predestination,

explaining that God did not create people in his own image and then condemn

some to perdition. According to Mayhew, people had free will to act morally or

otherwise. He preached the ethics of Jesus but insisted that God-given reason

reinforced them. His belief that Jesus derived his authority from God but was

not co-equal with God led him to view the doctrine of the Trinity negatively.

The Bible taught Mayhew that there was but one God,

the Father, who could not be divided into Son and Holy Spirit. The publication

of Mayhew's Seven Sermons in 1749 and their

circulation in Great Britain gained for him the degree of doctor of divinity

from the University of Aberdeen in 1750. The intense opposition of clerical

colleagues failed to silence him.

Mayhew believed that his mission was to ‘proclaim liberty’ from all forms of

tyranny. In response to the attempts of high-church Anglicans to make a martyr

of Charles I, in 1750—101 years after that monarch's execution—Mayhew preached

a ‘Discourse concerning unlimited submission … to the higher powers’. He

charged that rulers had no authority from God to govern unjustly. His sermon

was published immediately and distributed widely. It made Mayhew a leading

advocate of religious freedom. When members of the Church of England in the

1750s and 1760s urged the appointment of a bishop for the American colonies,

Mayhew vigorously opposed this. What he feared was the imposition of religious

qualifications for voting and office-holding that would exclude dissenters, the

levy of taxes to support Church of England clergy and bishops, as well as

episcopal political influence as prevailed in Britain. The passage by the

British parliament of the Stamp Act in 1765, which

imposed controversial direct taxes on internal American trade, provided him

with another opportunity to warn against the abuse of power. He announced to

his congregation that laws imposed without the people's participation reduced

them to slavery. When parliament repealed the act in 1766 Mayhew preached a

‘Thanksgiving’ sermon, ‘The snare broken’, in which he likened the American

colonists to birds who had escaped the hunters. He optimistically expressed the

hope that now God would permit his children to enjoy liberty for ever. In a

letter to James Otis he cautioned, however, that vigilance would be necessary

to maintain the colonists' freedom.

A short time later Mayhew served as scribe for a pastors' council that had

gathered to hear a neighbouring congregation's complaints against its minister.

The journey and the meeting left him exhausted. He suffered either a stroke or

a cerebral haemorrhage that led to his death on 9 July 1766. He was buried two

days later. He was survived by his wife, who later married his successor,

Simeon Howard, and a daughter. Another daughter and a son had died in infancy.

Mayhew's thoughts and actions were precursors of what was to come. His

political and religious beliefs were those of the Enlightenment, which was

becoming increasingly influential among colonial American intellectuals. Although

others, such as Mayhew's Boston colleague Charles Chauncey, endorsed the

theories of Isaac Newton and John Locke, no one advocated them more forcefully

than Mayhew. He was the forerunner of American Unitarianism. By resisting

arbitrary rule in church and state, he contributed to the coming of the

American War of Independence.

John B. Frantz

C. W. Akers, Called unto

liberty: a life of Jonathan Mayhew, 1720–1766 (1964) · C. K. Shipton, Sibley's

Harvard graduates: biographical sketches of graduates of Harvard University,

17 vols. (1873–1975), vol. 11, pp. 440–72 · C. Wright, The beginnings of

Unitarianism in America [1955] · C. Bridenbaugh, Mitre and sceptre:

transatlantic faiths, ideas, personalities, and politics, 1689–1775 (1962)

· C. Rossiter, ‘The life and mind of Jonathan Mayhew’, William and Mary

Quarterly, 7 (1950), 530–58 · W. B. Sprague, Annals of the American

pulpit, 8 (1865); repr. (New York, 1969), 22–9

Boston University · Hunt. L. | Mass. Hist. Soc.,

Thomas Hollis MSS

J. Greenwood, portrait,

1747–52, Congregational Library, Boston · T. Hollis, etching, 1767 (after

portrait by J. Singleton Copley (?)), Mass. Hist. Soc.

bequeathed to widow £800:

Akers, Called unto liberty, 111–12

![]()

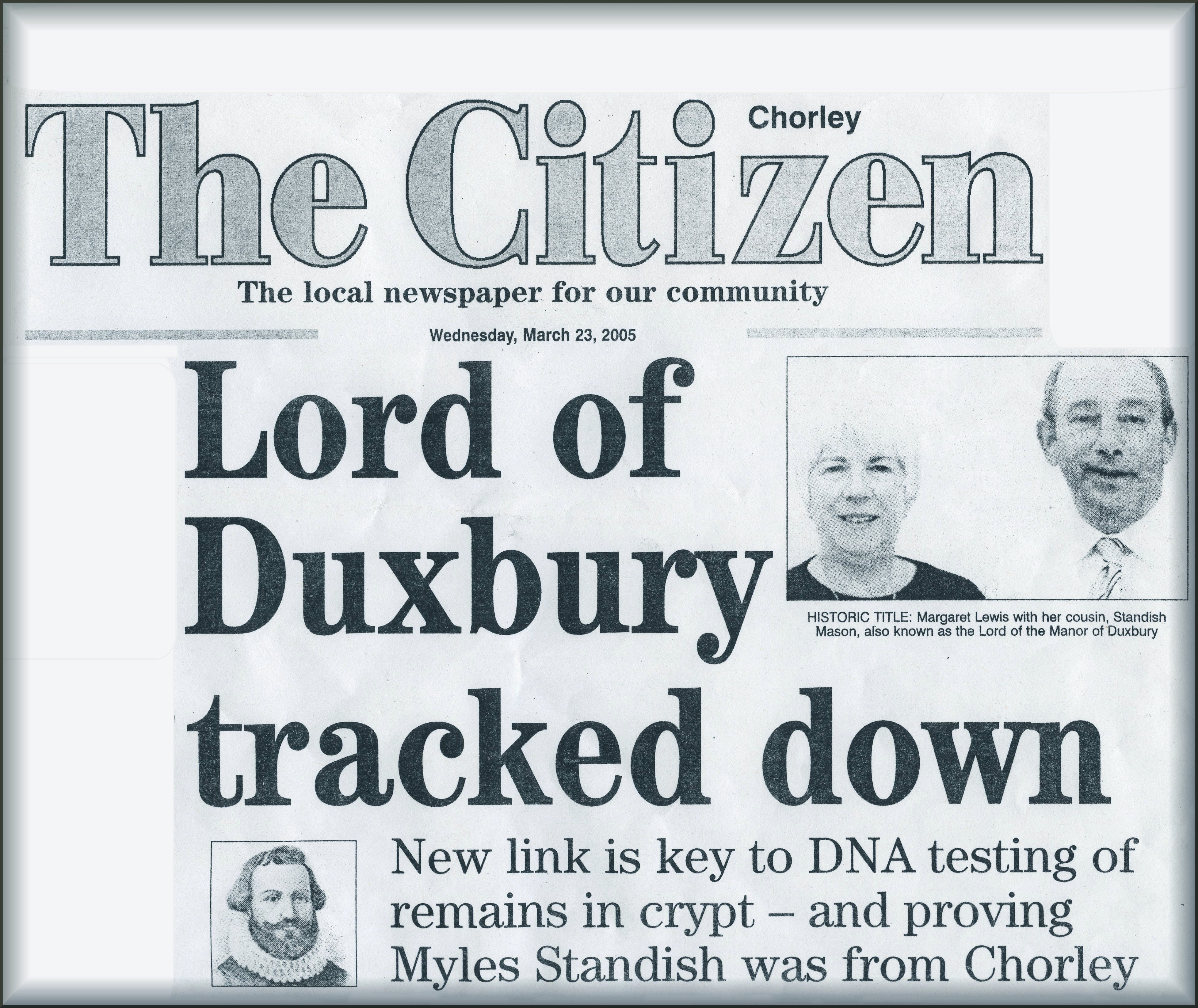

2008. Standish Mason of Dublin Ireland. lord of the manor of Duxbury.

A man who couldprove once and for all that one of the American founding fathers was from

Chorley has been tracked down.

Descendants of the Standishes of Duxbury were brought together at a recent festival celebrating the town's links with Myles Standish, the

Pilgrim Father who captained the Mayflower

on its voyage of discovery in 1620.

The event was part of a long-running project

by St Laurence's Historical Society to reclaim

Myles Standish from the Isle of Man which has built up a tourism

industry around its alleged links to the US

founder.

Among those attending the festival was

Margaret Lewis from Stockport, whose cousin descends from the eldest male line

of the Standishes.

Aptly named Standish

Mason, his geneology has been traced back and, as an eldest

male descendant himself, he is even

entitled to call himself Lord of the

Manor of Duxbury.

He is also believed to hold the burial rights

to the Standish family crypt at St Laurence's Church,

which could be crucial. As holder of the burial rights, Mr Mason would

be able to petition church authorities to open up the crypt to allow DNA tests which — if matched with Myles Standish's

American descendants — could prove definitively that Myles was from Chorley.

Mr Mason, 63, was informed of his newfound title and historical significance this week.

He said: "I was amazed when I learnt that

I had claim to the title.

"I was aware of my family history but had

no idea that I was linked so strongly with Myles Standish.

"I would like to come over to Chorley and

co-operate in any way I could, whether it be DNA tests or a bid to open up the

family tomb."

Local genealogist, Tony Christopher, who

worked on the family tree for St Laurence's Historical

Society, said: "The title of Lord of the Manor of Duxbury doesn't

entitle Mr Mason to any property.

"But, as the eldest male in the family, I

do think he will have the burial rights to

the family crypt. We have contacted two people in the US who have pedigrees

back to Myles, and if we can cross reference the DNA from the remains in

the crypt to them, then it will prove that Myles originated from Chorley."

The news has caused a ripple of excitement

across the borough, among historians and local residents alike.

Reverend John Cree of St Laurence's said:

"It's so exciting that many strands of the Myles Standish story have come

together after the recent festival and there is much of interest for us to look

into further."

And church warden Ed Fisher, who has helped to

co-ordinate the project, said: "This is marvellous news, hopefully Standish

Mason will prove the final part in this amazing jigsaw puzzle."

Rev Cree said that church authorities would

need to be petitioned to access the crypt.

"The first step will be to contact the

registrar of Blackburn Diocese," he said.

"And from there it

will go on to an ecclesiastical court in London along with the

Home Office."

If proven, the news could have massive

implications for tourism in the borough and elsewhere.

At the moment, many Americans travel to the

Isle of Man, which has exploited its alleged

links with Myles Standish.

If it is proven that Myles was in fact from

Chorley, the whole Standish tourist trail will have to be re-mapped.

Chris Mellon cultural services spokesman for Chorley Borough Council, said: “The discovery

of Standish Mason could be important in establishing Chorley's links with

Myles”.

"It is certainly interesting that he has

claim to the lord of the manor title and the burial rights."

EXCLUSIVE by Chris Gee

Link: The final years of the Manor of Duxbury part 2 .

![]()